BY GILLIAN MACDONALD

SCOTLAND'S WORTHY BEAST

Scotland’s Worthy Beast

When you think of Scotland, what comes to mind? Vast rolling hills with a million sheep grazing the fields, or overtaking a lone car on an empty road out of nowhere in a wild traffic jam? Men wandering the forests in tweed jackets and hats? The overwhelming number cashmere shops lining the Royal Mile? That strange meat pudding of a national dish that Scots are so very proud of, haggis? All of these images have one thing in common: they are all somehow connected to sheep. There are currently around 30 million sheep in Britain today, which amounts to roughly half the human population of the UK. The seemingly innocent animals have a long and complex history in Scotland, of which I was interested in trying to understand during my residency at Edinburgh Food Studio. Throughout my stay in Edinburgh, I spent my time reading and talking to people as much as I could about sheep in Scotland. Not only did I learn about the historical development of the Scottish heritage breeds of Scotland and how they have shaped the national landscape, but also about the experiences of heritage farmers today and how we as researchers and consumers can help ensure heritage breeds are kept alive.

While doing this research, I wanted to make sure I met with farmers who were breeding heritage breeds to understand the landscape of Scottish sheep farming today. I talked to them about their experiences breeding, why they chose to raise the breeds that they did, what they struggle with, and how they work to overcome these issues.

Middle image: Soay Sheep, Kirkton Cottages. Photo: Gerald Lincoln

Right image: Jack Cuthbert of Ardoch Hebridean.

Hebridean, Slipperfield Crofts, Photo: Gillian MacDonald

Hebridean, Slipperfield Crofts, Photo: Gillian MacDonald Castlemilk Moorit, Craigencalt Cottage, Photo: Ron & Marilyn Edwards

Castlemilk Moorit, Craigencalt Cottage, Photo: Ron & Marilyn EdwardsThough native breed farmers have many reasons for choosing these sheep, they are also faced with a load of troubles. Though hardy and able to survive on rough ground, because of this most native breeds are quite small and slow growing. Jane Cooper, a breeder of Boreray sheep based in Orkney, explains that the island sheep are “best eaten as mutton when they’ve achieved their full size after 3 years.” This can cost much more than breeding sheep for lamb, as farmers have to calculate costs of keeping an animal for 3 years rather than 6 months to 1 year. It used to be valuable to keep sheep for long periods of time, as farmers could make a pretty penny off of their fleece each year, hence the value and popularity of mutton prior to the industrial revolution. However, as the wool trade declined after WWII, mutton was not cost effective. “Now there is a crisis among hills sheep farmers, and those on remote Scottish islands, who must get better prices for their mutton if they are to survive. They have vast areas of rough grazing which is ideal for nothing much else than rearing mature sheep,” Catherine Brown explains in Scottish Cookery.

Native sheep breeds are also exceptionally seasonal. Most people do not understand that meat, especially from small producers and especially in the North, is highly affected by seasons. Lambs need to grow until they are of a certain standard, and mutton needs a summer feeding in order to make sure they are healthy and have enough meat on them when eaten. Mutton should be available in Scotland from October to March, though different farmers may have different timing. For example, North Ronaldsay are best after winter because storms have washed up so much seaweed. The main issue is that the sheep should have access to nutritious summer and autumn forage, so they are able to put on a bit of fat before they are killed.

Further, because most native breeds are small, they do not meet standardized market sizes and struggle to be sold for the same prices a standard commercial sheep breed would get through supermarket suppliers. Because there’s no established market for meat and fleece, most farmers have to find their own avenues for selling their produce.

Farmers have been working around these struggles in a variety of ways. One such way is by forming cooperatives and using their breed societies as an avenue for centralization. Breed societies have been trying to work with producers to create spaces to make selling easier. One example of such a cooperative is the partnership founded between Seriously Good Butchers and a group of Hebridean farmers to create the Hebridean Sheep Cooperative. Since most Hebridean farmers in the local area only breed small flocks, the cooperative gives each breeder the opportunity to have a designated week where they bring their animals. All of the slaughter, butchering, and marketing is taken care of by the Butchery. This partnership and centralization allows small breeders to cope with their lack of consistent supply. The Hebridean Sheep Society have also been working with the wool board to get all of their wool centralized and branded, so there is a constant supply which can be marketed properly.

In terms of wool, the Natural Fibre Company is a good example of this type of cooperative. Because many farmers struggle to sell their wool for a sustainable price, and many do not have the resources to process wool into yarn to sell themselves, the Natural Fibre Company will work with farmers of specific breeds to purchase their fleeces in collective batches and partner with mills to process it into craft-grade yarn for knitting or weaving. This way, farmers don’t have to seek out independent weavers to sell their fleece to, or sell their fleece for low prices to larger, industrial boards.

In order to work around these barriers, provenance is key to farmers being able to market their meat and wool. In an article on sheep farming in Shetland in the publication 60 North (2014), Ronnie Euston, a prominent Shetland sheep breeder explains, “It’s always been my position that not having it available in the supermarkets means that you can have individual retailers still in business. As soon as the supermarkets get a hold, you’re into cost-cutting, you’re into threatening the viability of your local shops, and you’re into local shops being obliged to import meat.” By working with local shops or specific butchers, farmers attempt to build a traceable network so people can guarantee that the produce their purchasing is from local sources. “We have the story, we have the culture, we have the tradition,” Euston says when speaking of the Shetland Islands, which can be used to their advantage.

This support can be expanded further, and building more relationships is key. One example of this type of relationship-building would be to focus on better supply chains for “premium mutton products”, connecting farmers, abattoirs, butchers, proper mail delivery systems, farmers markets, and chefs.

The recent closure of Orkney’s only abattoir highlights how incredibly important every role in this supply chain is in connecting sheep farmers with customers. Because abattoirs are so few and far between, the closure of the Orkney abattoir has been disastrous for many small farmers in the area, including the entire flock of North Ronaldsay sheep. Boreray sheep farmer Jane Cooper explained what this closure means for her, saying “my business is at a standstill because Orkney abattoir closed with no notice in early January. Months of campaigning and research later and still no idea what's happening for the next couple of years.” In order to have a supply of North Ronaldsay sheep for the year, the farmers had to get 186 sheep on the ferry over to the Orkney mainland (which only runs one day a week in the wintertime), and transfer the sheep in the same day onto the overnight ferry to Shetland. They had to rest on the island over the next week before going to the small Shetland abattoir. Cooper explains how incredibly lucky this trip was, as the North Ronaldsay ferry had been cancelled for 6 consecutive weeks in the past due to weather and tides. Ideally, North Ronalsday would have had 220 to 240 sheep go to slaughter over a winter, however with the closure of the local abattoir there is no idea what the future holds or how the local farmers will be able to sustainably bring their sheep to slaughter. Long journeys to abattoirs far away can also affect the quality of the meat. Cooper explains, “stress isn't only a welfare issue; it affects meat quality even at low levels of stress hormones. One reason I suspect that the Boreray [is well liked] is [because of ] its texture. We had a system that meant they were as relaxed as is possible for the short journey to the abattoir, being unloaded by me, handled by the amazing Brian (sheep whisperer) in lairage, and stunned and killed by skilled staff soon after we dropped them off. If we can ever get not only a proper small abattoir in Orkney but mobile units to go round the isles, I suspect the texture of North Ronaldsay will improve.”

Another valuable place to focus is more government support for conservation grazing. Currently there is no proper funding system set up for farmers wanting to expand into conservation grazing. One farmer spoken to was able to rent out a piece of land from the Forestry Ministry, who was trying to promote the re-growth of a peat bog through grazing. However, because they didn’t have proper subsidies in place, there was no proper incentive for the farmer other than promoting biodiversity for the environmental sake of it.

In terms of the food industry, this relationship building can be supported through more understanding of the limitations of working with small breeds (i.e. size and seasonality), and through trying to work past market standards through further understanding of taste.

Using research to do our part

This is where our research comes into the picture. Based on the background research, we decided that we could use our further research capacity to explore taste through conducting a sensory analysis of native Scottish mutton in order to create flavour descriptors that farmers could use in their marketing. We wanted to do this in order to give native sheep producers and suppliers a way to understand the complexity of flavours in their meat, which they can then use to build and grow on their market.

We collected 9 legs of all of the native sheep breeds we could get our hands on from around the country, and one day last September we invited a group of tasters from around the Edinburgh community together for a day to taste and analyze the samples we were able to get our hands on.

We decided to focus our research on mutton because we had heard from many farmers we spoke to that the flavours of the meat are much more developed in mutton, and as quite a few of the smaller breeds take a while to grow to a reasonable size, they are best eaten as mutton.

We connected with farmers all around Britain, from the Lake District to all the way up in the Orkney Islands, who were breeding pure-bred Heritage Scottish breeds, and bought a leg of ewe mutton off of each of them. The 9 breeds collected included: North Ronaldsay, Boreray, Scottish Blackface, North Country Cheviot, Castlemilk Moorit, Wensleydale, Shetland, Hebridean, and Soay.

By September, all of the legs were with us and we were ready to hold an event at the restaurant to taste them.

We cooked all of the samples in the same way, putting them in a brine solution overnight and cooking them in a sous-vide water bath, all at the same temperature, all for the same time. We then cooled them down to room temperature, sliced them into bite-sized samples, and randomized them with some spreadsheet magic. This way, each participant got a different sample order, and a different sample number for each slice, in an attempt to minimize bias as much as possible. The plate they received ended up looking a little like this (See left)

Fig 1: Table of Descriptors

Fig 1: Table of Descriptors Fig 2: 9 year old participant

Fig 2: 9 year old participant Fig 3: Results

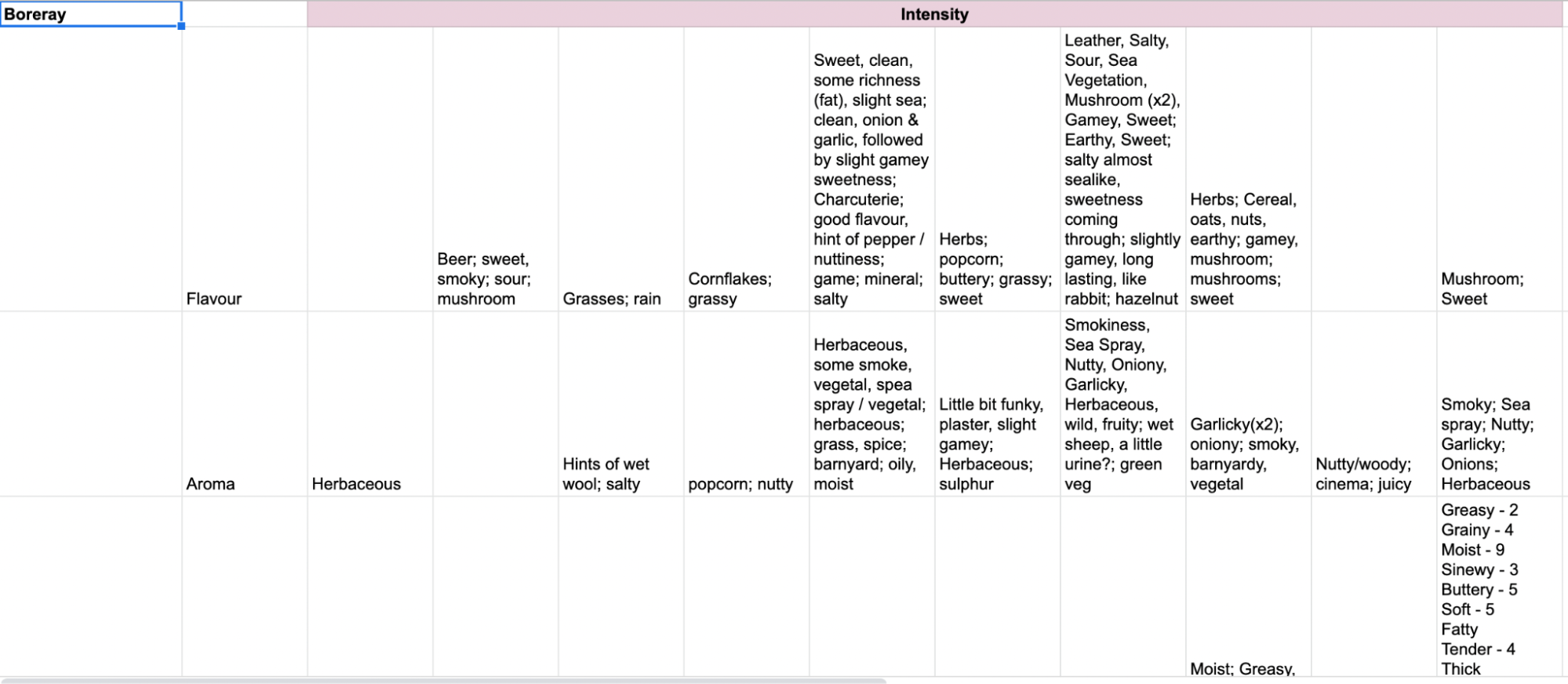

Fig 3: ResultsFor our sensory analysis, we didn’t want to focus on what the best or worst types of mutton were, but more so on the diversity of the tastes involved. For this reason we chose to use a “free choice profile” test. For each sample, a participant would have to judge it based on the “flavour”, “aroma”, and “texture” on a sliding scale from “most intense” to “least intense”. We asked them to get creative and describe the flavours, aromas, and textures on the scale. If they needed help, we had a table of descriptors they could use as inspiration. (Fig 1)

We invited people from around the community, young and old, and from all different walks of life. We had chefs, food writers, statisticians, software developers, retired doctors join us. Our youngest participant was a 9 year old who listed their profession as P5 student. (Fig 2)

We even had a group of the farmers who we had spoken to over the past few months join us for the tasting, two of which were suppliers of our samples. We just missed the delivery cut off for the weekend for two of our sample legs, so one farmer travelled up the day before to hand deliver us two legs all the way from the Lake District. It just goes to show how dedicated and passionate about their products many of these farmers are.

In the end, we had 27 participants come out that day to take part in the research. Everyone filled out their randomised sample sheet, and afterwards we discussed which sample was which breed, and everyone told us which one they thought were there favourites. There were a few front runners, including Shetland and Boreray, but many people had very subjective preferences of tastes they liked and tastes they weren't so keen on. And if you were wondering, the farmers that came were not able to recognize which breeds were theirs.

Though participants weren’t necessarily “experts” in tasting, and some hadn’t even tasted mutton before, they were all excited to learn about the differences in the variety of breeds and the ranges of tastes there were. One of the most unexpected but pleasant parts of this research project was learning that opening up your research to the public fosters a sense of community. It brings people together in a space where they can learn, interact, and connect with the products and the people who produce. The more research projects we open up, the more we can foster engagement and education about the food around us.

The end results ended up looking a little like this (see Fig 3)

We took all of the analyses from each participant and pored over them, putting them all into a spreadsheet and trying to make sense to see if there were any patterns we could see being formulated.

See graph below:

It was brilliant to see such a wide variety of incredibly creative responses, including “autumn afternoon”, “a mouthful of parsley”, “a coastal path (up north, not Fife!)”, “wet wool”, “forest floor”, and “fireworks”, to name a few. We took all this information and did two things with it. As we planned, we wanted to come up with a set of flavour descriptors that farmers and chefs alike could use to help them describe tastes of different breeds. Below you can see a graph which displays the wide variety of tastes that were identified through each sample.

Along with this “flavour graph”, we were able to identify certain flavour and aromapatterns that could be connected to each breed sample. We collated the top three tastes for each breed and put togethe a “breed flavour profile”, that has the potential to be used by consumers who are interested in sourcing breeds based on their flavour profiles. After some feedback from farmers on how the information on texture may also be a valuable resource for them, we decided to add this as well.

We hope this research can be used by farmers, chefs, and consumers alike to help them explore and emphasise the diversity of breeds found around the country.

As we tracked down all of the breeds, we decided to combine this research project with an art project. As sheep are a key part of the food history and agricultural make-up of Scotland, they are also vital to the textile history of Scotland. We tracked down a skein of natural yarn from each breed, and combined them into a knit wall hanging that will be able to be found in the restaurant. The colours and textures of the sheep breeds represented can be seen to be equally as diverse as their tastes. They range from white, to grey, to brown, to black; rough to fine and delicate fibre.The pattern is inspired by the traditional cable patterns that were created by fishing communities around the British isles. Each community would have specific patterns used to identify their fishermen in case one was ever lost at sea. The breeds, from top to bottom, are: Soay, Wensleydale, Castlemilk Moorit, Cheviot, Hebridean, Boreray, North Ronaldsay, and Shetland.

To wrap up, we thought we’d include a bit of a historical “recipe”, explaining how mutton has been preserved in Scotland in past centuries:

Mutton ham, though rare in modern days, were popular throughout Scotland because of the relatively low numbers of pigs and abundance of sheep. In the 1700s, mutton hams could be found throughout the Scottish Borders as a local specialty and were even exported internationally from Glasgow.

In Shetland, there were multiple ways of curing mutton throughout history. Before salt became a popular preservative, ‘Vivda’ mutton was a popular way of preservation. ‘Vivda’, meaning ‘leg meat’ in old Norse, would simply be hung to dry in order to be preserved. The meat would be dried in square buildings on the coast called ‘Skeos’, which were specially ventilated in order to allow the salty air to blow through. This process would have to be done in cold and windy weather to ensure that no flies or bacteria would get to the meat, and the meat would be hung to dry there for 4-5 months. Though the Skeos huts can be found on the island today, Vivda is not, however it is still consumed as a delicacy on the Faroe Islands.

When salting became more well-known, Shetlanders further developed their drying skills by producing Reestit mutton. In this process, the cuts of mutton would be put into a brine with salt and sugar (one butcher has described it as 80% salt and 20% sugar; elsewhere it has been described as adding enough salt until a potato can float) for 10 to 21 days, after which it would be hung to dry in the rafters of the house above a peat fire. The smoke would season the meat. Reestit mutton, popularly considered as Shetlands ‘national’ dish, can be found in the houses of many Shetlanders still today and can be purchased through local butchers, including Globe Butchers in Lerwick.

Bibliography & Acknowledgements

Kennard, Bob. Much Ado about Mutton. Merlin Unwin Books, 2014.

Brown, Catherine. Catherine Brown's Scottish Cookery. Drew, 1985.

Holmes, Heather. Scottish Life and Society: a Compendium of Scottish Ethnology: Institutions of Scotland: Education. Tuckwell Press in Association with the European Ethnological Research Centre, 2000.

A special thanks to Richard Briggs, Jonathan James, Jack Cuthbert, Ron & Marilyn Edwards, Gerald Lincoln, Jane Cooper, Maria Benjamin, and all other farmers and butchers who helped supply our samples for their endless knowledge, generosity, and support without which we never would have been able to make this project happen.